The rise of Nollywood and Korean cinema is yet another product of globalisation. Global Film has become exponentially more prominent in the last few decades and it is the film industries of Nigeria and South Korea that have become the newest members to join the plethora of nations who are paving their way towards mainstream cross-cultural cinema.

Nigeria’s film industry, known as ‘Nollywood’, is in fact the third-largest film industry in the world. It produced a whopping 1,687 films in 2007 – and an average of 50,000 copies of these films are sold at Nigerian shops and market stalls after their release. However, Nollywood has remained relatively enclosed within the African market, as most North American and other Western audiences are still oblivious to the enormity of this $3 billion film industry. The more that is learned about Nollywood, the more impressive it becomes; with its recent birth in 1992, this industry has rocketed to success in a mere 23 years. The founder of Nollywood is credited to Kenneth Nnebue, whose film Living in Bondage was shot in just one month on a budget of $12,000. Nevertheless, the film sold over 1 million copies and created the foundation of an industry that has not only provided entertainment, but has become one of Nigeria’s “largest sources of private-sector employment.”

The key to Nollywood’s success in Nigeria is its inherent locality; as affirmed by Okome, it explicitly caters to Nigerian audiences through the employment of Nigerian actors, Nigerian settings and its exploration of Nigerian issues. However, the styles in which Nollywood films are shot do have an indisputable global flavour, such as the common employment of melodrama paralleling that of Latin American ‘telenovelas’. This unique blend of global culture may well be Nollywood’s ticket to Western success; with 10 Nollywood related titles already available on Netflix, Nollywood has embarked on the steady climb towards global triumph within our ever-growing context of globalization.

“Nollywood is commercially-savvy. It values the entertainment of its clientele.” – Okome

Korean cinema has also been extremely successful, especially in recent years. The Korean economic boom of the 1990s created space in the Korean market to invest in filmmaking and revitalise the industry whose difficult history, matches that of the nations tumultuous past. Today, the Korean film industry is experiencing a period of incredible success. It is the 7th largest in the world and has a huge rate of cinema attendance. Not only are Korean films popular, but they have also achieved a great level of critical acclaim – one of the most notable achievements has been Chan-wook Park’s Oldboy, which was awarded the Grand Prix prize at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival.

Extending from film, Korea has become Asia’s leading creator and exporter of pop culture. Described as the ‘Korean Wave’, phenomena such as K-Pop have stormed worldwide markets, with concert tickets to bands such as SHINee selling out “within minutes” in the UK and US. As a result, Korea has become somewhat of a ‘Queen Bee’ within Asia, which has provoked a considerable power shift in its relationships with China and Japan.

“To many young people, ‘Korea’ stands for fashionable or stylish. So they copy the Korean style.” – Wang Ying on Chinese youth

Hence, Global Film is an incredibly powerful tool in enabling the promotion of a nations culture. It also serves as a platform for further cultural exchange and through it’s complex process of production and distribution – allows many different aspects of other cultures to be applied and thus, a cross-cultural product to be created.

REFERENCES:

Bright, Jake. ‘Meet ‘Nollywood’: The Second Largest Movie Industry In The World’. Fortune. N.p., 2015. Web. 3 Sept. 2015.

Okome, O (2007). ‘Nollywood: spectatorship, audience and the sites of consumption’ Postcolonial Text, 3.2, pp. 1-21.

Onishi, Norimitsu. ‘A Rising Korean Wave: If Seoul Sells It, China Craves It – The New York Times’. Nytimes.com. N.p., 2015. Web. 3 Sept. 2015.

Paquet, Darcy. ‘A Short History Of Korean Film’. Koreanfilm.org. N.p., 2015. Web. 3 Sept. 2015.

Ryoo, W. (2009). Globalization, or the logic of cultural hybridization: the case of the Korean wave. Asian Journal of Communication, 19(2), 137-151.

Rice, Andrew. ‘The Making Of Nigeria’S Film Industry’. Nytimes.com. N.p., 2012. Web. 3 Sept. 2015.

Rousse-Marquet, Jennifer. ‘The Unique Story Of The South Korean Film Industry’. inaglobal. N.p., 2015. Web. 3 Sept. 2015.

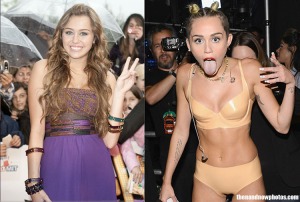

lieved wholly what ‘the media’ had to say. So why do I claim not to? I believe that it has become fashionable to antagonise the rather elusive umbrella of ‘the media.’ To put it simply, we use the media as a scapegoat to avoid acknowledging our own role in allowing the immoral actions of the media to perpetuate. Those few who admit their unwavering allegiance to the words of the media are characterised as uneducated buffoons and are almost looked upon with a kind of pity, as if they haven’t caught on to a rather obvious secret. Yet in reality, is anyone immune to the media’s vacuous pull, despite our unending claims to know better? It seems the media has become our newest ‘frenemy;’ something we ‘bitch’ about relentlessly, yet will be dragged back to by the ankles at the hands of inescapability. Even as a media student myself (a new one, in my defence), I admit I will scoff in the face of headlines that question whether size 12 Christina Aguilera has “let herself go”, whilst I simultaneously Google how many calories are in peanut butter. This brings me to my wise old dad’s biggest anxiety about the media, “that it’s so powerful.”

lieved wholly what ‘the media’ had to say. So why do I claim not to? I believe that it has become fashionable to antagonise the rather elusive umbrella of ‘the media.’ To put it simply, we use the media as a scapegoat to avoid acknowledging our own role in allowing the immoral actions of the media to perpetuate. Those few who admit their unwavering allegiance to the words of the media are characterised as uneducated buffoons and are almost looked upon with a kind of pity, as if they haven’t caught on to a rather obvious secret. Yet in reality, is anyone immune to the media’s vacuous pull, despite our unending claims to know better? It seems the media has become our newest ‘frenemy;’ something we ‘bitch’ about relentlessly, yet will be dragged back to by the ankles at the hands of inescapability. Even as a media student myself (a new one, in my defence), I admit I will scoff in the face of headlines that question whether size 12 Christina Aguilera has “let herself go”, whilst I simultaneously Google how many calories are in peanut butter. This brings me to my wise old dad’s biggest anxiety about the media, “that it’s so powerful.”